Built & Natural

Heritage

A comprehensive collection of the world's most significant cultural heritage sites, with detailed documentation of threats, preservation efforts, and historical context.

33

Total Sites

9

Critical

1

Threatened

11

At Risk

12

Vulnerable

0

Safe

Acropolis of Athens

A complex of monuments accumulated over centuries on a plateau that has been the sacred and political heart of Athens since the Bronze Age, crowned by the Parthenon, one of the most refined and influential buildings in the history of human architecture.

Adam's Peak (Sri Pada)

Adam's Peak — Sri Pada, the Sacred Footprint — is a 2,243-metre conical mountain in the Sri Lankan highlands whose summit rock formation is venerated as a sacred footprint by four of the world's major religions simultaneously. For over a thousand years, pilgrims of all these faiths have climbed 5,500 steps through the night to reach the same summit at the same dawn, making it one of the oldest continuously shared sacred sites in the world. The mountain's surrounding cloud forest is a biodiversity hotspot containing over 150 endemic plant species found nowhere else on earth.

Amazon Rainforest

The most complex and biodiverse terrestrial ecosystem on earth, containing approximately 10 percent of all species on the planet within 5.5 million square kilometres of living forest, home to approximately 400 Indigenous nations speaking around 300 languages, holding an estimated 150 to 200 billion tonnes of carbon in its biomass and soils, and currently approaching a scientifically projected tipping point beyond which large areas may transition irreversibly toward savannah.

Ancient Kyoto

Ancient Kyoto encompasses seventeen historic monuments across three cities — temples, shrines, palaces, and gardens that constitute Japan's most complete surviving expression of imperial court culture. Japan's imperial capital for over a thousand years, it received 50 million visitors in 2019 — ten times its resident population. The machiya, traditional wooden townhouses that once formed the domestic fabric of the city, are disappearing at approximately 2% per year, taking with them the living trades — textile dyeing, lacquerwork, confectionery — that give the monuments their cultural context.

Angkor

The most extensive low-density urban complex of the pre-industrial world — a religious and administrative capital of the Khmer Empire that at its twelfth-century peak may have supported a population of up to one million people across an urban footprint of roughly 1,000 square kilometres. At its core stands Angkor Wat, the largest religious monument on earth, alongside hundreds of temples, reservoirs, hydraulic works, and urban infrastructure distributed across a landscape that has only recently been mapped to its full extent by aerial LiDAR survey. The hydraulic systems that sustained the city's population are simultaneously its greatest engineering achievement and the focus of its most urgent conservation science.

Attirampakkam

A stratified sequence of stone tool assemblages spanning approximately 1.5 million years, from the earliest known Acheulean handaxe technology in peninsular India through a transition to Middle Palaeolithic technology that appears — according to radiometric dating published in 2018 — significantly earlier than the same transition in Africa and Europe, potentially before the dispersal of anatomically modern humans out of Africa and challenging fundamental assumptions about the cognitive and demographic history of early humans in South Asia.

Baghdad

For five centuries the intellectual and political capital of the Islamic world — a city of libraries, hospitals, observatories, and markets that drew scholars, merchants, and diplomats from across Eurasia. At its Abbasid height it was, by most estimates, the largest city on earth. Its House of Wisdom preserved Greek philosophy, advanced mathematics and astronomy, and produced original work in medicine and optics that would not be surpassed in Europe for centuries. Very little of that city survives. What does survive is concentrated in four historic areas — Old Rusafa, Al-Karkh, Al-Adhamiya, and Al-Kadhimiya — containing 132 formally listed monuments within a fragile urban fabric now threatened by conflict damage, institutional failure, infrastructure collapse, and climate change.

City of Valletta

Valletta is among the smallest capital cities in the world and arguably the most concentrated — a 55-hectare baroque fortress peninsula built by the Knights of St John after the Great Siege of 1565, containing more cultural monuments per square metre than almost any other city on earth. Its most urgent conservation challenge is not the crumbling of its limestone but the emptying of its streets: the resident population has fallen from 20,000 in 1960 to around 5,800 today.

Galápagos Islands

An archipelago of 19 major islands and dozens of smaller ones, rising from three converging oceanic currents at the intersection of the Pacific, Nazca, and Cocos tectonic plates, isolated from the South American mainland by nearly 1,000 kilometres of open ocean. The islands contain one of the world's highest concentrations of endemic species — animals and plants found nowhere else on earth — including marine iguanas, flightless cormorants, Galápagos penguins, giant tortoises, and Darwin's finches, whose adaptive radiation across the archipelago provided Charles Darwin with the observational foundation for the theory of natural selection. The ecological integrity that makes these species possible is under accelerating pressure from invasive species, climate change-driven ocean warming, and the tourism and fishing economies whose growth has outpaced the management capacity of the institutions responsible for protecting the islands.

Great Barrier Reef

The largest living structure on earth — an intricate lacework of 2,800 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching 2,300 kilometres along the Queensland coastline, supporting 400 coral species, 1,500 fish species, six of the world's seven sea turtle species, and roughly 30 marine mammal species including dugongs. It is the only biological system visible from space with the naked eye, and by almost any ecological metric the most significant marine ecosystem on the planet. It is also, by any honest measure, a system under severe and accelerating stress.

Great Wall of China

The Great Wall of China is not a single wall but a 21,196-kilometre system of walls, fortifications, watchtowers, and garrison stations built over more than two millennia. It is one of the greatest construction projects in human history, built at incalculable human cost. A 2012 government survey found that 74% of its Ming-era sections have been damaged or destroyed — most through the quiet, centuries-long process of rural communities using its bricks as a quarry.

Göbekli Tepe

The oldest known monumental religious architecture on earth, built by hunter-gatherers approximately 11,600 years ago — 7,000 years before Stonehenge — whose T-shaped limestone pillars decorated with high-relief animal carvings have rewritten the prehistory of human civilisation and forced a fundamental rethinking of the relationship between religion, social complexity, and the origins of agriculture.

%3Amax_bytes(150000)%3Astrip_icc()%2Filluminated-goreme-vilage-1257203775-24f1e33358684bbfa4f711c7131a6489.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

Göreme National Park and Rock Sites of Cappadocia

Cappadocia is a landscape carved by ten million years of volcanic eruption and erosion into fairy chimneys, cliff faces, and deep valleys into which Christian communities carved entire cities from the living rock. The Byzantine cave churches of the Göreme valley contain some of the finest fresco cycles of the Middle Byzantine period, preserved by the same tuff that now vibrates each morning as up to 200 hot air balloons float above them.

Hampi

A 26-square-kilometre open landscape of approximately 550 monuments distributed across an extraordinary terrain of stacked granite boulders along the Tungabhadra River — once the capital of the Vijayanagara Empire, one of the wealthiest and most populous cities on earth in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Temples, bazaars, royal pavilions, elephant stables, and sacred tanks appear across ridgelines and around corners in a landscape that feels less like a heritage site and more like a civilisation that forgot to fully disappear. Large sections remain in active religious use, as they have been for over a thousand years.

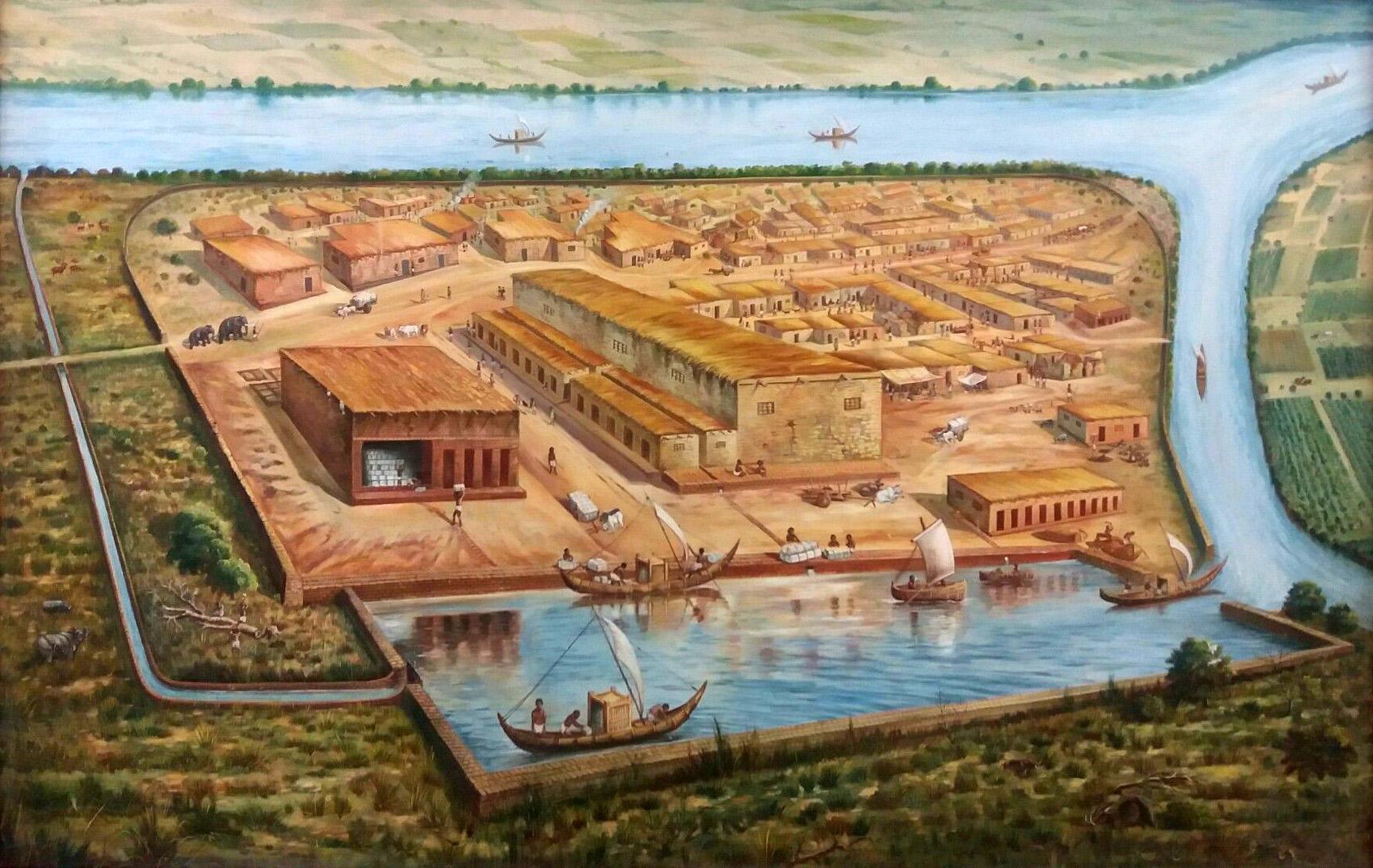

Harappa

One of the two great cities of the Indus Valley Civilisation, a Bronze Age urban culture that at its height was probably the most populous civilisation on earth, organised around a level of urban planning sophistication — standardised brick dimensions, grid streets, elaborate drainage systems — that remains remarkable even in comparison with much later achievements, and whose undeciphered script represents one of the outstanding unsolved problems of ancient linguistics.

Hierapolis-Pamukkale

Pamukkale — Cotton Castle in Turkish — is a thermal spring site where calcium carbonate-rich waters have built travertine terraces of luminous white over hundreds of thousands of years. Above them sits Hierapolis, a Graeco-Roman spa city with a complete theatre, one of the world's largest Graeco-Roman necropoleis, and the Plutonium — a cave confirmed in 2013 to emit lethal carbon dioxide concentrations that ancient writers understood as a literal entrance to the underworld and that modern tourists enter with the same cameras they use everywhere else.

Historical City of Florence

The city where the Western Renaissance was born, Florence contains within its 505-hectare historic centre a concentration of art, architecture, and urban fabric that has no parallel anywhere in the world, from Brunelleschi's dome to the Uffizi, from the Baptistery to Santa Croce, all now under severe pressure from overtourism and the recurring threat of Arno flooding.

Liang Bua Cave

The limestone cave on the island of Flores where the skeletal remains of Homo floresiensis — a previously unknown species of small-bodied hominin that coexisted with anatomically modern humans until approximately 50,000 years ago — were discovered in 2004, one of the most significant palaeoanthropological findings of the twenty-first century, whose implications for understanding the diversity of hominin species and the routes of human dispersal through Southeast Asia continue to be debated and investigated.

Lothal

The southernmost major site of the Indus Valley Civilisation and home to what is widely considered the world's oldest known artificial dock — a tidal basin measuring 218 by 37 metres, lined with kiln-fired bricks, that demonstrates the maritime capabilities and long-distance trading reach of a Bronze Age civilisation four thousand years ago, now facing coastal erosion, sea level rise, and the dual pressure of inadequate conservation resources and a major new heritage complex development.

Machu Picchu

A fifteenth-century Inca royal estate and ceremonial centre set dramatically upon granite outcrops at the crest of a cloud-forested mountain ridge in the Peruvian Andes, defined by sophisticated dry-stone masonry, terraced agricultural platforms, temples, plazas, and an extraordinary ancient water management system — positioned within a sacred landscape of mountains, rivers, and celestial alignments of profound cosmological significance to the Inca civilisation.

Old City of Dubrovnik

Dubrovnik is a perfectly preserved medieval and baroque city-state on a limestone headland above the Adriatic — the former capital of the Republic of Ragusa, which abolished slavery in 1416, established Europe's first quarantine system in 1377, and maintained its independence for 450 years through diplomacy rather than military power. In 1991 it was shelled by Yugoslav forces in an act of cultural terrorism that galvanised international opinion. Today it receives 4 million visitors a year for a resident population of 1,300 people.

Palmyra

A desert oasis city that became one of the most important cultural crossroads of the ancient world — a trading hub where Graeco-Roman, Persian, and Semitic civilisations met, fused, and produced an art and architecture of extraordinary distinctiveness. For two centuries the most significant trading city on the Silk Road between the Mediterranean and Mesopotamia, its ruins — colonnaded streets, a spectacular theatre, funerary towers, and the Temple of Bel — survived two millennia of desert isolation before suffering deliberate, systematic demolition by ISIL forces in 2015. The destruction, carried out over months and broadcast as propaganda, was one of the most devastating acts of cultural destruction of the twenty-first century. What remains is fragmented, unstable, and in need of conservation resources that have yet to materialise at the scale required.

Petra

A monumental rock-cut city carved into the rose-red sandstone of the southern Jordanian highlands by the Nabataean people between approximately the 4th century BCE and the 2nd century CE — a trading capital of extraordinary wealth and architectural sophistication that controlled the caravan routes between the Arabian Peninsula, the Mediterranean, and Egypt. Petra's defining achievement is the transformation of natural sandstone cliffs into an urban landscape of temples, tombs, colonnaded streets, and hydraulic infrastructure that reflects both an advanced engineering tradition and a cultural identity shaped by the convergence of Hellenistic, Egyptian, and Arabian influences. The site now faces a convergence of flash flood risk, physical weathering, salt damage, groundwater rising, and tourism erosion that the management systems in place have not yet fully addressed at the required scale.

Pompeii

The closest thing archaeology has to a time machine — a functioning Roman city of up to 20,000 inhabitants buried under four to six metres of volcanic material on 24 August 79 CE, preserving streets, frescoes, bakeries, taverns, and the postures of the people caught in the eruption in a condition that no deliberate conservation programme could have achieved, now facing a chronic structural conservation crisis that not even a 105-million-euro investment has fully resolved.

Rapa Nui

A small triangular volcanic island in the middle of the Southeast Pacific, the most isolated inhabited place on earth — 3,700 kilometres from the Chilean mainland and 2,000 kilometres from the nearest inhabited land. Famous for approximately 300 ahu ceremonial stone platforms and the moai ancestor figures they once carried, some reaching over 10 metres in height and 80 tonnes in weight, distributed across the island in a landscape-scale political and territorial system of extraordinary sophistication. The easternmost point of Polynesian settlement and the final destination of one of the most remarkable episodes of human navigation in prehistory.

Roopkund Lake

Roopkund is a glacial lake at 5,029 metres elevation in the Indian Himalayas containing the skeletal remains of approximately 800 individuals — visible when the ice melts in summer, scattered on the lake bed and surrounding slopes. A 2019 ancient DNA study found three genetically distinct population groups among the dead, including 14 individuals of Eastern Mediterranean ancestry dated to the 18th century CE at a remote Himalayan location. No explanation has achieved scholarly consensus. The remains are disappearing — removed by trekkers, dispersed by meltwater, exposed by retreating glacial ice — and there is no legal framework specifically protecting them.

Shanidar Cave

A large natural limestone cave in the Zagros Mountains of northern Iraq where ten Neanderthal individuals were discovered between 1951 and 1960, including Shanidar 1 — known as Nandy — whose survival to old age with severe injuries and disabilities implies sustained care by other members of his group, and Shanidar 4, whose associated pollen concentrations generated the famous flower burial hypothesis that transformed understanding of Neanderthal cognitive and emotional life, now critically threatened by armed conflict, looting risk, institutional fragility, and the environmental pressures facing one of the most geopolitically vulnerable heritage sites in the world.

Stonehenge

The most analysed and most visited prehistoric monument in the world, a series of concentric stone settings on Wiltshire chalk downland that encodes precise astronomical alignments and remains, after two centuries of scientific investigation, genuinely mysterious — the society that built it left no written record and the belief system that motivated its construction must be reconstructed entirely from physical evidence whose meaning is ultimately opaque.

Taj Mahal

The Taj Mahal is a mausoleum of white marble built between 1632 and 1653 by the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his wife Mumtaz Mahal, who died in childbirth. Widely considered the supreme expression of Mughal architecture, it is one of the most formally perfect buildings in the world. The marble is turning yellow from industrial pollution. Midges breeding in the polluted Yamuna River are staining it green and black. The wooden foundations beneath the minarets are drying out as the water table drops, and eight million people a year walk past.

The Colosseum

The Colosseum is the largest amphitheatre ever built — a monument of Roman engineering genius completed in 80 CE, capable of seating up to 80,000 spectators for gladiatorial contests, animal hunts, public executions, and staged naval battles. For nearly five centuries it was the empire's supreme theatre of spectacle and power. Today it stands as the most visited ancient monument in the world, straining under the weight of six million annual visitors, urban pollution, and seismic vulnerability.

Timbuktu

A city at the edge of the Sahara that was, between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries, one of the most important centres of Islamic scholarship in the world — a city of mosques, madrasas, and libraries that preserved and produced manuscripts numbering in the hundreds of thousands, many still surviving in private family collections and public archives. Its three great mosques — Djinguereber, Sankore, and Sidi Yahia — built of banco, the sun-dried mud brick that is both the city's defining material and its perpetual structural challenge, are the physical embodiment of a scholarly tradition that connected sub-Saharan Africa to the broader world of Islamic learning. The city now faces a convergence of desertification, jihadist violence, institutional weakness, and climate change that has placed it among the most acutely threatened World Heritage Sites in the world.

Venice and its Lagoon

A city built on water — 118 small islands connected by 400 bridges and divided by 150 canals, constructed on wooden piles driven into lagoon sediment, and home to one of the most concentrated assemblages of Renaissance and Byzantine architecture in the world. Venice was for four centuries the dominant commercial and maritime power of the Mediterranean, producing a distinctive civilisation that fused Gothic, Byzantine, and Renaissance influences into an urban form that has no equivalent anywhere. It is also, with increasing urgency, a city that is sinking into the sea it was built upon — subsiding by as much as 25 centimetres over the twentieth century while sea levels in the Adriatic simultaneously rise.

Çatalhöyük

One of the earliest and largest Neolithic settlements ever found, a proto-city that housed between 3,500 and 8,000 people from approximately 7500 to 5700 BCE, containing wall paintings, plaster reliefs, and burial deposits that have transformed archaeological understanding of how human beings first learned to live together in complex communities.